Picasso early Cubism

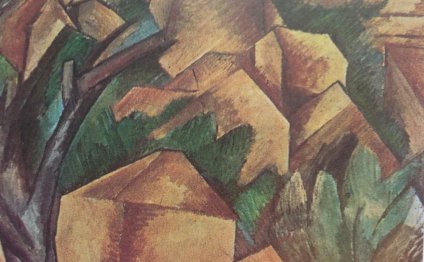

Whatever you believe you realize about Cubism, well, reconsider that thought. Picasso, Braque and Early movie in Cubism, which goes on at PaceWildenstein’s East 57th Street location through June 23rd, not only gathers collectively a staggering collection of masterworks from understanding probably the most crucial motion in contemporary art—it knocks a hundred years’s worth of received knowledge on its ear.

Whatever you believe you realize about Cubism, well, reconsider that thought. Picasso, Braque and Early movie in Cubism, which goes on at PaceWildenstein’s East 57th Street location through June 23rd, not only gathers collectively a staggering collection of masterworks from understanding probably the most crucial motion in contemporary art—it knocks a hundred years’s worth of received knowledge on its ear.

Bernice Rose, which curated the exhibition from (to estimate the pr release) “an original concept proposed by Arne Glimcher, ” features written a book-length catalogue essay attracting contacts between early movie together with paintings produced by Picasso and Braque from 1907 to 1914. But a sidelong glance at the films projected in discreet sides associated with gallery is truly all you have to have it. Such as the drop of liquid that converts absinthe from mint green to milky opalescence, the exhibition’s idea transforms your reception regarding the paintings in one stroke.

Although the PaceWildenstein press release generally seems to hedge its wagers, stating that “early film played a catalytic role in development of Cubism, but as an added level of reference that doesn't displace the canonical explanations and evaluation, ” the evidence associated with convention itself returns a quite different verdict. For one, it undermines the historical account (enshrined, it could seem, into the really term Analytical Cubism) that Picasso, under the influence of Cezanne’s monumental belated paintings and Braque’s abstemious state of mind, briefly abandoned their backsliding penchant for popular culture and artistic gags to create a string of Apollonian masterpieces. This event shows as an alternative that Picasso had been constantly Picasso, snickering at slapstick one-reelers and elbowing bad Braque in the dark, then heading off towards the studio to paint exactly what he saw. The genius of Cubism, to follow along with this type of idea, had been it adopted the projected picture as both content and kind. Within shifted framework, the Cubist topic, be it a portrait or still life, no further feels like an obsessive examination of kind in room, however the trajectory of a picture flashing at night eye too rapidly becoming recorded in mainstream terms. Cubism’s feature brushstroke—dashed off, quick and rectangular—rather than talking about Cezanne’s faceting of volume, appears to echo the dazzling rate of frames running right through the projector’s gate. Inside sense, Cubism anticipates Futurism but goes it one much better. In place of celebrating the literal velocity of machines hurtling through space once the expression of a unique century, it establishes a far deeper, much more metaphysical paradigm—that the actual subject of art in the modern-day period could be the nervous blur of the time.

Photo by: Genevieve Hanson/ Courtesy The Pace Gallery It is startling to see how much the cinematograph, the initial type of a movie projector, several samples of which are on display, resembles a Cubist mind. But this will be a sideshow compared with the formal and philosophical symbiosis between artwork and film, founded at cinema’s infancy, the exhibition indicates. Whilst the very early clips from Edison, the Lumière brothers, Méliès et alia included in the tv show may seem quaint, simplistic and more than a little silly, the feeling of question that enthralled their designers and audiences alike feels embedded within their silver nitrate shine. They are flickering patterns of light endowed with a Promethean capacity to manipulate man emotions—reflections of raw truth easily included within a physical and personal framework. In this regard, we may see the collage part of Cubism, especially the usage of paper scraps, as mirroring the shock of cinema’s unmediated images of everyday activity. We might in addition infer that Picasso and Braque, exhilarated and challenged by the dynamics of film, assimilated the new method by inverting it, from an illusion of room that exists only in time, to an illusion period existing in pictorial and physical space. Using this interpretation a step more, cinema can be seen as painting’s Platonic ideal, and, in its innovation of a new type expressing the slipperiness of this ideal, Cubism becomes a manifestation of meta-painting.

It is startling to see how much the cinematograph, the initial type of a movie projector, several samples of which are on display, resembles a Cubist mind. But this will be a sideshow compared with the formal and philosophical symbiosis between artwork and film, founded at cinema’s infancy, the exhibition indicates. Whilst the very early clips from Edison, the Lumière brothers, Méliès et alia included in the tv show may seem quaint, simplistic and more than a little silly, the feeling of question that enthralled their designers and audiences alike feels embedded within their silver nitrate shine. They are flickering patterns of light endowed with a Promethean capacity to manipulate man emotions—reflections of raw truth easily included within a physical and personal framework. In this regard, we may see the collage part of Cubism, especially the usage of paper scraps, as mirroring the shock of cinema’s unmediated images of everyday activity. We might in addition infer that Picasso and Braque, exhilarated and challenged by the dynamics of film, assimilated the new method by inverting it, from an illusion of room that exists only in time, to an illusion period existing in pictorial and physical space. Using this interpretation a step more, cinema can be seen as painting’s Platonic ideal, and, in its innovation of a new type expressing the slipperiness of this ideal, Cubism becomes a manifestation of meta-painting.

Beyond the electric fee delivered by its idea, Picasso, Braque and Early movie in Cubism is an exceptional chance to bask in sheer visual delight of several of Picasso and Braque’s most astounding works. Even although you don’t purchase its concept, the exhibition’s cinematic dimension transports a method of painting frequently considered austere and forbidding into something that’s lyrical and buoyant, also fun. With an off-the-charts ratio of masterworks per sq ft of partitions, and a handsome, hardcover catalogue, this show would-be considered museum quality if perhaps most museum exhibits were this original, or this damn good.

—Thomas Micchelli

SUGGESTED ARTICLES

by Hovey BrockRELATED VIDEO

Share this Post

Related posts

Cubism Picasso

Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) at your workplace, c 1905. Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis Today, 17 July 2012, is the…

Read MoreItalian painters 19th century

Throughout the 19th century, Italian painters were engaged in the major imaginative moves of that time period. Neoclassicism…

Read More